Reflections

The Tale behind ‘Mishkenot Sheananim’

The very first settlement to be built outside the walls of the Old City, Mishkenot Sheanim was founded by the benevolent Sir Moses Montefiore – and paved the way for the expansion of Yerushalayim beyond its walls

In spite of its small size, Yerushalayim was held dear in the eyes of its inhabitants; many vied for a space within its walls to call their own. Jews, Christians, Moslems and Armenians lived side by side in densely crowded streets, which was a breeding crowd for disease and sickness. The congestion also caused a dearth in available livelihoods for the residents of the city.

It was during that difficult period that the wealthy philanthropist Sir Moses Montefiore came to visit the Holy Land. This was his fourth visit; on his previous visits he had already bestowed much needed assistance to the needy Jews of the land, particularly those in Yerushalayim. However this visit was slightly different, since he now carried with him the enormous sum of fifty thousand dollars, donated by a wealthy Jew named Yehuda Touro for the cause of the holy land.

Yehuda Touro was a Jewish American businessman who passed away with no heir. In his early years he was somewhat distanced from his Jewish heritage, despite the fact that he came from a prominent religious family and his father served as a famous Chazzan. In his later years however he drew nearer to Torah observance, and after his death he bequeathed the staggering sum of two-hundred thousand dollars for various Jewish causes, of which fifty thousand dollars was to be funnelled into causes in the holy land. One of the trustees responsible for the implementation of his will was Sir Moses Montefiore, and he now arrived in Eretz Yisrael with the express intent of carrying out the final wish of his friend, and helping the Jews of the Land.

Montefiore’s original plan was to acquire land outside the walls of the Old City and build a Jewish hospital to serve the residents of Yerushalayim, so that they would not have to avail themselves of the non-Jewish hospitals - many of which were run by missionaries. This plan was discarded later when it was clear that people were not willing to use a hospital outside of the city walls, because of the inherent danger. When Montefiore realized this, he changed his plans and decided to erect a spacious Jewish settlement on the ground that he had purchased outside of the city walls. The first stumbling block he faced was the Turkish law which forbade foreign citizens such as Montefiore, who was of British nationality, to acquire land in the Ottoman Empire. In order to circumvent this problem, Montefiore made a stop-over on his voyage and visited the capital of the Ottoman Empire – Constantinople, where he sat with the Sultan and obtained from him an official permit that would allow him to buy land in Eretz Yisrael. Armed with this document, Montefiore arrived in the holy land in the year 5615 (1855), and began to look around for a suitable plot of land to build his visionary hospital.

After some time he found a suitable plot above the ‘Sultan’s Pool’, which belonged to one of the rulers of Yerushalayim, Ahmad Aga Izrad. After negotiations that lasted an entire day, the two sides agreed to a compromise and Moses Montefiore deposited the sum of one thousand Sterling Liras into the hands of the Arab ruler, in exchange for the coveted piece of land. Three days later, on the 1st of Elul 5615 (1855) the corner-stone of what was to be the first Jewish settlement outside the walls of the Old City, was laid.

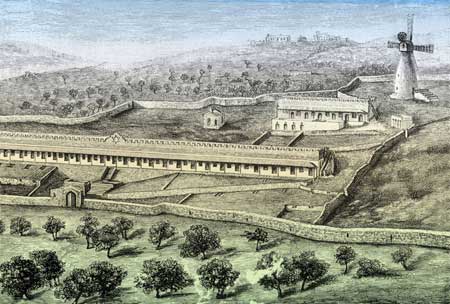

Montefiore’s untiring efforts on behalf on his needy brothers did not cease, and in order to provide the destitute of Yerushalayim with a livelihood he recruited many Jewish artisans and constructors to help with the building of the new settlement. Only when it was clear that there weren’t enough Jewish laborers was he willing to call upon non-Jewish workers. The original building of the neighbourhood consisted of one long structure which contained sixteen apartments. The apartments were spacious relative to the standard living conditions at the time, with each apartment consisting of two rooms and a kitchen, and a small private garden. Aside from this Montefiore oversaw the building of two Shuls – one for those of Ashkenazik descent, and the other Sefardi; and a Mikveh (ritual bath-house). At a later stage another building was constructed in the settlement, which would contain four additional apartments.

The settlement was considered particularly modern and progressive; the spacious apartments were the dream of every resident in Yerushalayim. A well was dug inside the settlement, from which water could be drawn with the aid of a modern hand-pump as opposed to manually drawing up the water with buckets. The crowning glory of the settlement was, without a doubt, the famous wind-mill that was built in its center. With a goal towards helping the Jews of Yerushalayim support themselves with a respectable livelihood, Montefiore instructed his workers to build a flour-mill that would grind flour by way of wind-power. To this end he invited an expert from England who was proficient in all aspects of the wind-mill industry, and he toiled over the plans and oversaw its construction until it stood upright and worked efficiently. The wind-mill did indeed achieve its purpose, and brought about a marked decrease in the price of flour in the Holy City. A number of years later the windmill ceased functioning as more modern mills were erected in the city, which were driven by steam as opposed to wind. At that point it wasn’t financially worthwhile to keep the old mill running, but for the many years it stood in service it accomplished a great deal for the good of the city dwellers.

On the 18th of Cheshvan 5621 (1861) construction of the new settlement was complete, and the town was named ‘Chatzar Yehuda Touro’. Later, in order to encourage people to move to the new settlement its name was changed to ‘Mishkenot Sheananim’, according to the verse in Sefer Yeshaya – ‘And the people sat in a peaceful dwelling, and in safe houses, and in tranquil peace’. According to Montefiore’s plan, the settlement was intended for the poor of Yerushalayim and the distribution of the apartments would be in the domain of the various ‘Kollels’ which were active at the time in the Old City. The chosen residents were originally supposed to live in the new apartments for only three years, whereupon they would vacate the settlement and make way for new residents. Montefiore wished that as many people as possible would benefit from the spacious apartments. However in reality the demand for these new apartments was low, since most people were wary of moving to a new settlement beyond the city walls, and as a result the apartments were given permanently to those who agreed to leave the Old City. The main problem that would face these dwellers and which in turn deterred others from moving there, was the safety issue – in an area teeming with Arab trouble-seekers and without the reassuring presence of the ancient walls, it was a justified fear. The settlement was surrounded with fences and its gate was locked every night, yet still many desisted from moving to the new dwellings in spite of its tempting comforts and trappings.

After the First World War and the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, the British ruled over Eretz Yisrael. This was a particularly harsh period for the residents of ‘Mishkenot Sheananim’, but it was precisely then that the settlement was joined by several new settlements built nearby: ‘Machane Yisrael’; ‘Nachalas Shiva’, ‘Meah Shearim’. The additional Jewish presence in the area did not stop Arab rioters from attacking the residents of Mishkenot Sheananim and the other settlements. A further difficulty that arose after the Great War was the cessation of foreign support that had reached the settlement on a regular basis until then. Despite these considerable difficulties however, the settlement continued to exist in pride, and the ‘new Jerusalem’ outside the city walls grew and flourished.

After the historic decision by the United Nations to divide the Land, the British instructed the residents of the settlements to vacate their houses and the Arabs would move in. The Jews refused and clung to their homes, and over the years continued to strengthen their boundaries until after the establishment of the State of Israel. At the end of the War of Independence the boundary line between Israel and Jordan moved adjacent to the settlement, and the residents suffered for nineteen years from the fire of Jordanian sharpshooters who were perched on the city walls, and who would deliberately target the residents of the town. They lived surrounded by walls of grey cement and coils of barbed wire, and this almost unbearable state of affairs caused many of the original dwellers to leave the place. In their place, Jews who had been driven out of the Old City came to live there, as well as new immigrants.

In the course of the Six Day War, the city of Jerusalem and additional territory to its east until the Dead Sea was recaptured from the Jordanians, and the Old City and the new were united into one great city. The border was now far from ‘Mishkenot Sheananim’, which returned to be a place worthy of its name. The settlement itself has undergone countless renovations since those far-off days, and today serves mainly as a tourist site. The main building serves as a conference center, and nearby stands the ancient wind-mill in its full glory - having become one of the historic symbols of Yerushalayim. To the side of the wind-mill, in a glass room stands a fully restored version of Sir Moses Montefiore’s personal chariot.

The settlement Mishkenot Sheananim was a breakthrough to the ‘new Jerusalem’, being the very first settlement to be built outside of the walls of the Old City. May we soon merit to see the expansion of Jerusalem ‘until Damesek’, as the Navi promised us, with the coming of Mashiach speedily in our days.